It was obvious to me that my students had suspect ideas about note-taking. What was not so obvious to me that I have some deeply ingrained assumptions about it too.

The following is my attempt to describe a small investigation I carried out with my Psychology classes. Whilst the results were not what I expected, I can genuinely say that it has made a significant difference to what I do on a regular basis in my lessons.

Objectively, most of the ‘findings’ in this project were things I knew already. However they hadn’t all struck home. Some of my long-established teaching habits needed a bit of a shake-up. I’ve read lots of research based advice about teaching which in theory should have meant I didn’t need to learn this particular lesson.

Ironically, this little episode of ‘discovery’ teacher learning has led me to adopt a more ‘traditionalist’ approach to my teaching.

The challenge:

I have a number of well-meaning pupils whose approach to studying defers learning (i.e. understanding and committing to memory) to an undefined future date. Within a lesson, their end goal is having the right answers written down rather than necessarily knowing them. It seems to me that this obsession with recording information correctly once, gets in the way with the messier (and ideally iterative) reality of learning new material.

It seemed fairly clear to me for with some of my own students, ‘thinking hard’ has become detached from the act of writing. As a result time spent studying does not always lead to much learning.

I had a cunning plan. A simple experiment could prove to my students just how futile their approach was.

The results were entirely opposite to what I expected.

The context:

I have three year 12 Psychology groups. Each has a lesson on Wednesday and Thursday.

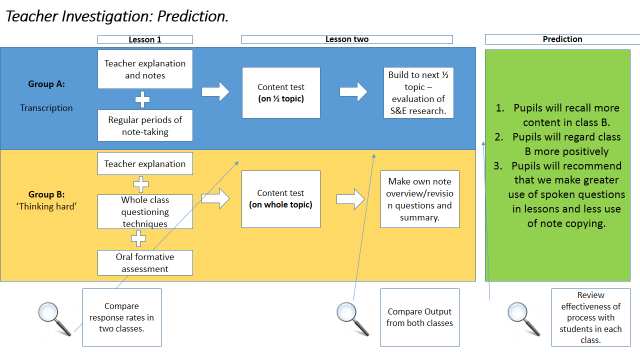

On Wednesday, I would teach one class using mindless transcription and the other using a series of challenging questions which they needed to be able to answer to show they understood the material.

The following day would include a short test and the second half of the content for Group A and a short test followed by a chance to write up their own revision notes for the faster moving Group B.

The material in question was the methods, findings and conclusions of Schaffer & Emerson’s research into the carer and infant attachment process.

I predicted that transcription would presumably not add much to pupil learning though it would slow the lesson down. Thus I would expect the group learning in this way to cover less ground and remember no more of it than the class which didn’t waste time writing neat copies of their notes booklets.

Things did not go as expected.

Process:

In Group B’s lesson pupils:

- Answered questions about attachment (verbally: in pair, in groups, and as a whole class)

- Explored why it was being researched

- Designed our own study to review attachment stages in a group of infants

- Compared this with Schaffer & Emersons’s own version

- Reviewed their findings and the stages of attachment which they developed.

There were regular questions; some ‘pair and share’, some open, some randomly selected using lollipop sticks. This was all reinforced with a 3 minute video summary which we then discussed. We also had time to explore some of the strengths and limitations of Schaffer and Emerson’s research.

Pupils enjoyed the lesson and several thanked me afterwards.

In Group A’s lesson:

They covered similar ground but stopped (for 5 or 6 minutes) on 5 separate occasions to copy answers into their books.

As a result we didn’t get as far (barely fitting in the overview video and not considering the strengths or limitations).

Furthermore the lesson was quite ‘boring.’ Lots of writing. During the writing slots it was clear that a range of writing/thinking speeds produced considerable differences in how much was actually written down. For both of these reasons I didn’t feel that it was very successful and would have been concerned if it was being graded on the grounds that there were no palpable buzz in the room.

When my third class entered I gave them a quick schpeel on the experiment and invited them to choose which group to join. They joined Group A.

Test:

The next day all students carried out a ‘purple pen challenge.’ In this task students are given a coloured pen (no prizes for guessing the colour) with which to quickly jot down what they remember about a previous topic. After 5 or 6 minutes the purple pens are collected in and students use a different colour to add to what is missing/correct any errors using their notes and questions to peers or teacher if necessary.

The results were surprising – to me anyway.

Findings:

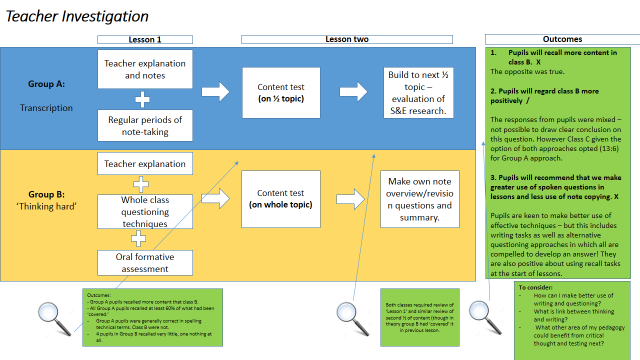

The students in Group A all remembered at least 60% of the content. They also were mostly able to spell key names (Schaffer & Emerson) and used more technical language in their points.

In Group B there was one student who remembered more than anyone – we had ‘covered’ more content. The rest of the group did not fare so well. Over half (10 pupils out of 18) remembered 50% or less. Four students seemed to be able to recall nothing at all.

The penny dropped for me when one of these four expressed surprise at her inability to remember anything.

‘That’s weird I remember the lesson, remember talking about Schaffer and Emerson and the video….it was really good. I just can’t remember anything in specific’

Outstanding. I thought. And – do you know I think in the bad old days the lesson could well have been given that badge.

It seemed unreasonable to continue the trial – also Group B needed to re-cover the same material again. I stopped the experiment and am still exploring the implications for my own teaching.

Reflection:

So where did it all go wrong? Why was my smugly developed attempt to weed out pointless writing scuppered by its own results?

On reflection I’ve decided the following two are plausible explanations.

1. Poor operationalization. I wanted to test excellent questioning vs mindless transcription. I probably actually tested reasonable questioning without any drawn out written questions vs regular writing of written answers – though pupils in Group B were using their course-notes when writing, they were doing so to answer questions in at least 5 of the 6 writing episodes.

2. My questioning and neat-writing free lesson was not as good as I (and some of the students) seemed to think. On reflection I think that even the pair and share questions allow wiggle room or students to opt (or check) out for a spell in a way which written questions do not. In a repeat test I would like to allow them to use a sheet of scrap paper to jot down short answers/points/words which is then recycled afterwards – removing panic about whether it’s correct/neat enough etc.

On balance I think it was too easy to opt out of my more interactive lesson and this was compounded by a pace which may have appeared buzzy but which only one student managed to keep up with.

I’m still thinking about why I seem to conflate writing with boring. Does the spectre of boring writing say more about my own assumptions and motivators as a teacher than it does about effective lesson activities. Probably.

I’ve been reading Willingham’s ‘The Reading Brain’ and am interested in its implications for the lesson activities which I choose to use. In particular here the linking of spoken words with written ones seemed to leave some of my pupils better placed when writing about the lesson later on. Since the experiment and my reading I am making much more use of collective reading, and carefully considered writing tasks at regular intervals in my lessons.

Furthermore I’ve become more aware that there are large elements of my practice which I could do with rationally re-considering. Not because I’m a terrible teacher, but because I could be a better one and the only way to achieve this would be by changing what I do.

What next?

This year I’m trying to avoid spending all my time exploring theoretical cul-de-sacs in order to make practical improvements and additions to the techniques I regularly use in lessons. These will include the following, which I will review and outline in future posts.

- More consistent use of the ‘purple pen challenge’ as a means of encouraging recall and review of previous content.

- Question chains

- Regular writing in response to carefully considered questions.

- Comparative assessment tasks – both digitally and in lesson.

- Learning to make better use of ‘knowledge organisers’

- Class reading and annotation.

- Identifying and supporting students who work more slowly than others (and why the word ‘differentiation’ is potentially unhelpful).

- The envelope challenge.

Alongside this I’m interested how enjoyable, surprising (perhaps only to me), and motivating this short process was. I enjoyed discussing the idea with colleagues and sharing the lessons I learned throughout the process. I also felt that through it I became a little more self-aware of my own motivators and biases. Since this episode I’ve already developed two or three new approaches for my Psychology and Sociology lessons (which is rather more than I normally manage at the back end of term 1).

Is there a place for simple experiments in CPD programmes?

For a while I thought not. Mainly because the ‘findings’ are almost inevitably limited in the reliability and validity departments. However, in this case I’ve learnt something about my own classes in a way which has provoked significant changes to my practice.

Maybe it was seeing the way in which several students in one group lagged far behind their peers in the other. This genuinely concerned me and made me think about the cumulative impact of sitting in lessons like the first one – which, for years I taught (and was encouraged to promote).

On one level at least, I ‘knew’ most of it already, but something about the process of evaluating my own teaching and student answers seems to have really struck home. Maybe this is is the real value of ‘teacher research’ it shook me up enough to question decade long habits.

Post-script

I tend towards being an ‘ideas person’ and with that can find following through with any of these ideas more challenging (and less interesting) than coming up with them. However, since writing this post – and without consciously returning to the list of ideas – I’ve found myself incorporating 6 of the 8 above ideas into my lessons on a regular basis. More support perhaps for the idea that teacher research can lead to practice changes in a way that traditional CPD might not.

Leave a comment