Why school improvement is a ‘wicked problem’ and how understanding may this help inoculate us against irrational responses to the latest Ofsted framework.

NB: An earlier version of this article was published in School Leadership Today (July, 2019).

Place Your Bets

Some of these things could happen in English schools in response the new Ofsted framework. Which do you think are most likely?

■ Scrapping use of ‘internal data.’ Because Ofsted no longer will be asking to look at it.

■ Retention of the majority tracking and monitoring systems which facilitate identification of, and intervention with underperformers.

■ Imposing ‘interleaving’ onto schemes of work. As Nick Rose of Ambition Learning Institute warns, while it may be potentially helpful,‘this idea can give rise to the potential “lethal mutation” that it’s best to chop-and-change different topics from lesson to lesson in order to achieve this spacing.’

■ Blanket use of knowledge organisers. A resource with merit in some contexts may not necessarily be appropriate in others – Maths or Dance for example. In some schools, a drive for homogeneity may lead to reduction in the quality of resources.

■ Book Scrutinies may have unintended consequences, as the link between written work and teaching effectiveness is not as clear as we might assume. For example, in a CEBE case study from 2017, it appeared that an increased emphasis upon showing progress in books had the unintended consequence of discouraging students from taking risks for fear of making mistakes.

■ Staff being required to memorise particular curriculum rationale (implementation, intent, and impact) statements. Or being appointed head of intent, implementation or impact—perhaps all three, perhaps just one.

■ Schools neglecting aspects of pedagogy which do not fit in with the categories and approaches focussed on in this particular framework.

■ Rewriting schemes of work in order to please an audience of one. For example, I was recently asked to review a proposed curriculum redesign which framed RE around a series of possible careers—as ‘that’s what Ofsted want us to be able to show.’ Jesus’ miracle at the Wedding at Cana was included in the ‘events management’ topic.

It is highly likely that some of these things will likely happen in some schools. Such changes would be ill-advised and unproductive. However, it is not helpful to write them off as examples of irrational or misguided decisions by school leaders. They are predictable responses to the most recent attempt, at policy level, to solve the wicked problem of school improvement.

What are ‘wicked problems’ and why is school improvement one of them?

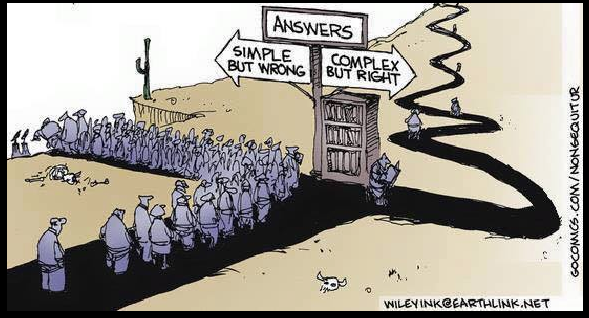

In policy research, ‘wicked problems’ are defined as social issues which are hard or even possible to define, to which solutions are not clear, and which cannot be fully solved.

Examples include financial crises, health care, income inequality and school improvement.

School improvement is arguably a ‘wicked problem’. It is impossible to fully solve, and the essence of the problem and plausible solutions to it, appear differently to every beholder.

Because we do not agree on the essence of the problem, neither are we likely to agree on how it should be tackled. As Rittel and Webber put it: ‘The analyst’s “world view” is the strongest determining factor in explaining a discrepancy and, therefore, in resolving a wicked problem.’ Or, as Maslow observed rather more pithily ‘I suppose it is tempting, if the only tool you have is a hammer, to treat everything as if it were a nail.’

Each concrete definition of a wicked problem includes within it an implied solution. Different definitions will imply different solutions.

The key point is that actors at different levels in the system hold to coherent (but different) explanations of the problem. These explanations each hold within them internally coherent (but different) solutions. This observation applies to school improvement.

■ A head teacher may define an aspect of the problem as one of recruitment – being able to employ the best possible teachers for each position in a school. Or they may consider it to be a CPD issue – that there is a need for high impact professional development.

■ A classroom teacher may decide that the problem is a lack of evidence-based pedagogy, a lack of creativity or a problem with the way that students behave within lessons.

■ An inspector may (in the old framework at least) have defined the problem in relation to the inadequate progress which some students make from their attainment when they join a school and the level it reaches when they leave.

■ A politician may link the problem to the soft bigotry of low expectations.

In other words, I may think that I am outlining the problem in objective terms. However, Bannink and Trommel (2019) suggest that my analysis will be bound to ‘what this actor would subjectively, consciously, deliberately, organizationally and personally decide.’ And that is tightly bound to the specifics of my own context, experience and understanding.

It is likely that my specific role and experience in education will affect the way I understand and propose to tackle the school improvement problem.

Accepting that school improvement is a ‘wicked problem’ and that any solution will not work as well as we would like could, ironically, help school leaders to respond positively and proactively to the changing Ofsted framework.

What makes school improvement wicked?

As argued above, it appears that school improvement is a wicked problem because:

■ The problem (and plausible solutions) will appear different to different beholders

■ We can’t possibly solve it

■ It regularly gets redefined

■ It is difficult or impossible to ‘be wrong’ (publicly at least)

Designating something as a ‘wicked problem’ may appear pessimistic but could be helpful in the long run.

We cannot possibly solve the school improvement problem.

A wicked problem is always linked to other problems, and will never be fully ‘solved’ by success in one area. This issue is captured poignantly in Nick Hanauer’s recent piece in The Atlantic in which he questions the ‘educationism’ he once subscribed to. In Better Schools Won’t Fix America, he writes that ‘like many rich Americans, I used to think educational investment could heal the country’s ills—but I was wrong.’

He notes that while 20 per cent of student outcomes can be attributed to schooling, ‘about 60 percent are explained by family circumstances—most significantly, income.’ His earlier belief in educationism has been dashed against the rocks of external family circumstances—which schools cannot directly influence.

However, despite their ‘wicked’ nature, these problems are significant and worth engaging with.

It is likely that, on balance, education does not have the impact that we wish it to. However, it does make a difference, and for those of us working in it, it is the primary means by which we can seek to make a positive mark on the world. Here, perfect cannot become the enemy of good. Perhaps acknowledging the complex dynamics at play may help us avoid either unrealistic expectations on the one hand and despair on the other.

Acknowledging that school improvement is a wicked problem involves accepting that perfect solutions do not exist. This could, ironically, be a helpful insight for school leaders. Firstly because perhaps a sense of ‘doing my best but never being good enough’ might be alleviated somewhat when we accept it would not be possible to be entirely fix a wicked problem. Secondly, it may help us to be reminded us that even the most meticulously developed ‘perfect’ strategies should not be expected to work perfectly. There will inevitably be a range of ways in which they do not transfer from plan to implementation as neatly as we would like.

School improvement is a wicked problem because it regularly gets redefined.

Wicked problems are regularly redefined. The act of redefinition rules out (and in) a range of solutions to the problem. This dynamic can be clearly seen in the way in which data use has shifted from being a key lever for school improvement to, in some contexts, a potential impediment to it.

Ofsted’s 2016 inspection framework stated that:

‘In judging achievement, inspectors will give most weight to pupils’ progress.

They will take account of pupils’ starting points in terms of their prior attainment and age when evaluating progress. Within this, they will give most weight to the progress of pupils currently in the school, … Inspectors will consider the progress of pupils in all year groups, not just those who have taken or are about to take examinations or national tests. (para 175)

‘[Inspectors will seek to identify whether] pupils are set challenging goals, given their starting points, and are making good progress towards meeting or exceeding these.’ (para 179)

The implicit message here is that good (or outstanding schools) will track and monitor individual student progress using earlier attainment as an indicator of where they ‘should’ be. Using a flight path model perhaps?

Interpretations of this line of inspection, including examples from positive Ofsted reports, consultants, ed-tech providers and school improvement organisations, probably all contributed to a boom in the range and frequency of inappropriate uses of data, as outlined in the DfE’s 2018 report: Making Data Work.

With the new framework, Ofsted are now categorically discouraging leaders from producing excessive data related workload. In a recent speech, Amanda Spielman addressed the issue of appropriate data usage:

‘I have similar misgivings about flight paths. The progress children make when they learn a subject is not necessarily linear. Progress should be measured by how much a child has learned of the curriculum, rather than when or whether they are hitting a particular target. …

And we certainly won’t need any further school-generated data relating to individual students or to closing gaps within classes or within the school. The data just isn’t particularly helpful here because the numbers of pupils are usually too small – another point made in ‘Making data work.’ …

If someone shows you a great big spreadsheet, you might want to ask who pulled it together and for what purpose. Who does the data help? Does it add value beyond what you’d get from talking to a teacher or head of department? Was it worth the time taken out of the teacher’s day to enter all those numbers?

This is the reality in which senior leaders work. They are tasked with realising the aims of policies (in this case the 2016 framework), which specify a necessary outcome (tracking pupil progress and showing that it is consistently good), but which stop just short of specifying exactly how this outcome could be achieved.

As school improvement was defined as pupils making adequate progress in ‘all year groups’, a key implied solution/action to achieve this became tracking and monitoring progress.

Interviews with staff in schools I visited during a data use and workload research project in 2017 illustrated the dynamic clearly. This senior leader, for example, felt compelled to produce graphs to help her answer Ofsted’s common lines of enquiry about progress.

‘I could be supporting teaching and learning but instead I am not looking at what makes teachers better but trying to draw a graph to prove we’re a good school.’

(Senior Leader, Primary School)

Ofsted have made significant moves to tackle the idea that school leaders need to do something for Ofsted—i.e. their myth-busting document. However, the very act of asking about in-year progress necessitates an answer or response. Arguably the same dynamic remains—though now with a curricular focus.

It is a wicked problem because ‘perfect solutions’ are appealing but inappropriate

The wicked problem perspective on school improvement perhaps explains the perennial problem of silver-bullets. Solutions which promise to neatly resolve educational problems, but fail to deliver.

Bannick and Trommel (2019) argue that when it comes to wicked problems, perfect solutions are unintelligent, as they implicitly assume that the problem itself is not ‘wicked’. In attempting to respond to a ‘wicked’ problem, organisations may adopt for a ‘perfect’ solution which promises more than it can actually deliver.

In the light of the ‘wicked’ nature of the school improvement problem and the accountability framework currently in pace for English schools, it is understandable that apparently ‘perfect’ but unintelligent solutions spread quickly whenever the frame changes.

The new Ofsted inspection framework points out that:

‘Through the use of evidence, research and inspector training, we ensure that our judgements are as valid and reliable as they can be. The judgements focus on key strengths, from which other providers can learn intelligently.’

(Ofsted, Education Inspection Framework, 2019).

It is intended that schools will review published judgements and learn intelligently from them. This improvement which is one of the rationale for having Ofsted reports.

However, it has been known to backfire—triple impact marking being a prime recent example. Once this exhaustive approach to marking—the clue is in the name!—was picked up in a positive Ofsted report, it spread across numerous schools far more quickly than a careful analysis of the evidence around marking (see for example this from the EEF) would suggest it merited.

There are a host of practices with the potential to repeat this recent history, either because they are have limited potential merit, or because implementing them at scale is rather more challenging (and slower) than school improvement cycles demand.

School improvement is a wicked problem because it is difficult or even impossible to be publicly wrong

Rittel and Webber (1973) pointed out that policy planners, unlike scientists, have no right to be wrong. Whereas ‘the scientific community does not blame its members for postulating hypotheses that are later refuted… In the world of planning and wicked problems no such immunity is tolerated.’ Policy planners are tasked with producing ‘perfect’ solutions to wicked problems. It is generally ill-advised to acknowledge limitations or even failure of a policy once it has been implemented. It would not be politically expedient to say that the earlier approach was wrong or failed in some areas.

This may apply to policy changes in education, perhaps explaining why Ofsted’s new framework—which includes significant differences to that which preceded it—is framed as an evolution rather than a revolution. It would not be politically expedient to frame it as the latter.

Changing goal posts

A similar dynamic may apply to the structures and policies within schools. They do not involve physical building but may have become integrated into the fabric of the schools to the extent that it is hard to question whether they are useful.

The awkward reality is that many schools have made decisions about how to structure their curriculum, allocate resources, and manage data which, until the end of this Summer term, fell well within the category of acceptable solutions to the school improvement problem (in relation to progress measures and the Ofsted framework). It now appears that the goal posts have changed. Whereas once the ‘perfect’ solution to school improvement could include a three-year KS4 and intricate data analysis systems, both of these are now subject to criticism. The pressure to reverse engineer rationale for these which fit the new framework is likely to be strong.

There are logistical pressures which might encourage schools to stick with the status quo. Job roles and resources may be tied up with it. However, here it is also worth reflecting on the way in which the level at which an actor works tends to inform their understanding of and solutions to a wicked problem. There may be significant personal costs to countenancing the inadequacy of a policy or process which one introduced across a school in a genuine attempt to improve things.

Furthermore, Ofsted have announced that there will be a year-long lead-in period in which schools can acknowledge the need to refine their curriculum focus in light of the new framework. The high-stakes nature of Ofsted’s judgement arguably make it extremely difficult for school leaders to acknowledge the limitations of earlier curriculum development decisions—which may have seemed prudent at the time but which now have fallen out of favour.

School leaders as always, face a significant challenge. On the one hand, quickly implementing ‘perfect’ solutions to the reframed problem is unlikely to be successful. On the other, carrying on without reviewing current practices and strategies—which may to some extent have been shaped by an earlier framing of the school improvement problem—is also not advisable.

To sum up, school improvement is a wicked, but vital problem. Understanding the dynamic of school improvement as such, and the range of pressures which it likely entails, may give school leaders the best chance of responding intelligently to it.

How is school improvement a wicked problem?

■ We don’t agree on the essential nature of the ‘problem.’ It can be (and is) answered in a myriad of ways. Each ‘way’ will imply a different solution.

■ The plausibility of a solution to a wicked problem lies within the eye of the beholder. Our perspective and frame of possible actions will likely influence the way we pin down the problem and identify what we deem to be a viable solution.

■ It is impossible to fully resolve a wicked problem. Improving schooling will never, in itself, resolve the socio-economic challenges with which it is often tasked. Accepting this can lead to pessimism or can relieve unnecessary anxiety and expectations.

■ Wicked problems are often reframed. When this happens, some solutions fall out of favour and others are implicitly or explicitly endorsed.

■ Perfect solutions will not work but are (often) not allowed to fail. Wicked problems are not amenable to neat solutions. Perfect solutions, at policy level and possibly in schools, need to be seen to ‘work’, or at least not to fail. This dynamic can discourage meaningful evaluation or iterative approaches to school improvement.

What can we do to tackle the challenges?

Bannink and Trommel (2019) make the following suggestions in relation to tackling wicked problems. The principles underpinning each may well apply for school leaders:

- Living with the problem. It may be helpful to accept that the core issues underlying wicked problems are, to some extent,‘a fact of life’. An example of this can be found in the problems associated with an aging population. Here it is easy to see that as we will always have aging and that there always will be some problems associated with it. This does not lead us to stop working on the problem but may avoid unhelpful pressure to fully result it. Perhaps this applies to education too? There will always be some students who are relatively disadvantaged, they will, on average, not find it as easy to learn as their more advantaged peers. Hence closing this sort of gap will be a perennial challenge, but one worth engaging with.

I would argue that accepting that I cannot totally solve the problem may help me stop worrying unnecessarily without dissuading me from trying to do the best job I can . I know that much of what I do will not work as well as I hope, but I also know that despite this, teaching can make some difference some of the time—I can maximise my (albeit small) impact by consistently doing my best and not giving up in the face of inevitable challenges and a degree of ‘failure.’

2. Trial and error or iterative development. It is not advisable to simply implement blueprint designs which, once created become solid structures—a rigid perfect (and likely unintelligent) solution. Somewhat starkly, Bannink and Trommel argue that policy implementation is not about making a better world by ‘solving problems’ along utopian lines, but,‘making the world a little less gruesome by learning from the mistakes we make in small-scale experiments’.

At school level, this suggests that muddling through—adjusting and tweaking new policies as we go along may sometimes be advisable, rather than an admission of failure or a weakness. For example, Termeer, Dewulf and Biesbroek (2019) suggest that identifying small wins—achievable successes which indicate progress towards an ideal outcome—can help in this regard.

In my experience of visiting schools as part of data and workload research those invested in reviewing and modifying the practices were more likely to avoid the excesses or statistical cul-de-sacs which now invoke Spielman’s ire! The principle of small scale trial and error seems sensible here—and an awareness that nothing works everywhere.

In contrast, where schools adopt a specific strategy which has ‘worked’ elsewhere there is a high risk of falling into the ‘perfect blueprint’ approach outlined earlier.

- The sociological imagination. Bannink and Trommel (2019) suggest that ‘intelligent governance requires reflexivity, in the sense that it considers other problem definitions than the ones suggested by administrative reason.’ Here we can challenge the ‘facts of the matter’ as currently presented at policy level. It is too simple to state that they are ‘wrong’. However, it is likely that it is merely one rational interpretation of the wicked problem of school improvement which makes most sense at a level somewhat removed from day-to-day classroom teaching.

The support which schools provide disadvantaged pupils, for example is one in which we can improve our provision by challenging the way in which disadvantage is framed. Whilst at national level it is true that PP students tend to attain less academically than their peers, at a classroom level there will be disadvantaged non-PP (Pupil Premium) students and relatively advantaged PP students. Reframing the problem by focussing on specific deficits—language, access to resources, parental support, etc.—may help us respond more intelligently. A number of schools seem to be adopting this approach. Doing so requires acknowledging that ultimately outcomes (especially for small groups) are not even close to being entirely in our control before then identifying what is, and then working hard at improving that.

Final thoughts:

It is likely that, on balance, education does not have the impact that we wish it to. However, it does make a difference, and for those of us working in it, it is the primary means by which we can seek to make a positive mark on the world.

My impression is that many could do with accepting the above. Too much time and mental energy is spent worrying about outcomes which are not directly controllable, or (more frequently) working under a panicked sense of personal inadequacy premised on the mistaken beliefs that it is possible to do the job (differentiation, interventions, uplifting B grades to C’s) perfectly. Ironically this kind of thinking can both discourage great teachers from doing well, and can promote the emergence of silver bullets.

On balance, I personally find this line of analysis liberating. However, I may be an outlier. Maybe it is better to believe in the impossible and strive to achieve it to ‘aim for the stars and reach the moon’ as it were?

I would rather stop worrying about whether highly variable and largely uncontrollable outcomes will fall as I need them to so that I can focus on improving, and having an impact where I can.

I also wonder whether it frees me from having to decide on likely outcomes for any of my students – accepting that it’s not entirely in my control may actually make me less likely to write anyone off (an act, in my own experience at least, of self-protection at least partly driven by despair that what I do didn’t seem to be working as it should).

I now expect nothing to work – at least not to the point of perfection. I also accept that when dealing with multiple individuals, my teaching will necessarily involve compromise and the occasional frustrating moment!

My challenge is to improve what I can to reduce the frequency with which this frustration occurs! At classroom level this involves refining my explanations, examples, questions, resources and course-design etc and working hard to promote a classroom in which students generally think-hard, ask questions, and learn.

As always, your responses and comments are welcomed!

Thanks to Jory Debenham and my two hugely helpful reviewers who helped iron out rambling earlier drafts of this. Your help in re-shaping the piece was much appreciated. Any residual rambling is very much of my own making.

If you enjoyed reading this you may also like this related piece on teachers, workload and well-being

Leave a comment